People who compulsively compare themselves to others are up to psychological mischief, to say nothing of the hurt they inflict on others. Self-defeat is built into this mental and emotional processing. People are making themselves miserable, yet they don’t even begin to realize or understand what they’re doing.

The act of comparing ourselves to others frequently produces feelings of being superior or inferior to them. Distinctions are made in terms of physical appearance, athletic ability, intelligence, popularity, and personality. Such comparisons are often painful, producing guilt and shame. Even when feeling superior, people are covering up their emotional identification with those they deem to be inferior. Racists are notorious for comparing themselves to others and feeling superior, while hiding from themselves an awareness of their emotional resonance with feelings of inferiority. The same principle applies to misogynists, xenophobes, and fundamentalists.

Everyday people, in myriad subtle ways, also fall prey to this inner process. Driven by inner conflict, this toxic comparing is like an emotional audit system looping continually in one’s unconscious mind. Not all comparing is unhealthy, of course. We do sometimes compare ourselves to admirable role-models for instruction and inspiration. From childhood, we also compare ourselves to those around us to enhance self-knowledge and our emotional and social intelligence. That’s all well and good, of course.

Toxic comparing, however, serves the unconscious purpose of fostering and maintaining unresolved inner conflict. This conflict comes at a high price because it produces feelings of being refused, deprived, controlled, helpless, criticized, rejected, and abandoned. Many people resonate with (or experience themselves through) psychological attachments to these unresolved negative emotions. This means that, despite their conscious wishes to be strong and positive, they’re pulled emotionally into dark places. This constitutes inner conflict, and it greatly helps to understand these deeper dynamics.

Consider a person who produces the comparative thought, “If she can do it, why can’t I?” This person could be searching inwardly for genuine, healthy motivation. Depending on the tone and emphasis of his thought, however, he could also be generating shameful self-recrimination for his alleged inability to perform at the same level as the woman to whom he’s comparing himself. He’s stuck in inner conflict, wanting to feel strong yet compelled to feel weak. Psychological insight can free him from this inner conflict.

Like slapping our hand while reaching for a second cookie, we need to catch ourselves in the act of making toxic comparisons. Inner watchfulness enables us to understand how we generate our own misery. People make toxic comparisons mentally, as well as through memories of the past and speculations about the future. We can do it visually, through the occurrences we take in with our eyes. We can do it in our imagination, too. We want to catch ourselves doing this harm to ourselves, in order to understand the compulsion to search our mind, memories, and environment for ways to nurse old hurts, shames, and grievances. This inner vigilance exposes what humanity has always hated to acknowledge, the degree to which we’re psychologically willing to recycle and replay inner conflict and suffer the negative emotions it generates.

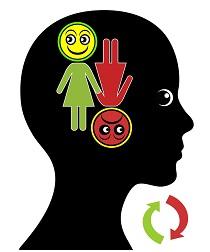

When we’re inwardly conflicted, comparing our self to others takes on emotional urgency. If we’re “not superior to the other,” the feeling goes, then we’re in danger of experiencing not just self-doubt but also self-criticism, self-rejection, self-condemnation, and even self-hatred. The conflict produces the sense of either-or, either good or bad. It’s a psychological polarity through which the inner critic dishes out self-reproach while inner passivity fails to protect us from the accusatory self-aggression.

Chronic comparing of oneself to others produces impressions of oneself and others that are misleading, biased, negative, and irrational. We won’t see others or ourselves objectively because we readily falsify reality to cope with inner conflict and to cover it up. A psychological defense, serving as inner denial, is activated, as for example: “I’m not interested in feeling unworthy or a lesser person. I don’t have that weakness. If anything, I enjoy feeling superior. This is what I want, this feeling of being better than others!” This defense, to be effective as self-deception that covers up one’s emotional attachment to self-criticism and self-rejection, requires that we start to feel scorn, even malice, toward those others to whom we feel superior. The defense operates unconsciously until, making it conscious, we can overcome our inner conflict and the self-debasement it produces.

When toxic comparisons produce a feeling of inferiority (in contrast to superiority), the individual, rather than fending off the inner critic’s judgment, is passively accepting it. In doing so, the individual absorbs punishment (guilt, shame, fear, depression) for the alleged “crime,” which is likely to be some infraction the inner critic is blowing out of proportion or even some false accusation.

On the surface of awareness, we can feel that our toxic comparing is rational behavior. Beneath the surface, however, we’re driven by inner conflict that makes it all compulsive. The compulsion is based on this psychological axiom: whatever is emotionally unresolved in our psyche—meaning whatever it is we’re inwardly conflicted about—is going to continue to be experienced by us, even when acutely painful and self-defeating. This inner process generates self-doubt, guilt, shame, self-criticism, self-rejection, depression, loneliness, helplessness, real or imagined failure, and many other symptoms.

As mentioned, comparing comes naturally from an early age. Starting with our parents and siblings, we define and orient ourselves—emotionally, mentally, and physically—according to how they interact with us and how we experience them. Unconsciously and consciously, we’re always comparing ourselves to them. We acquire a sense of who we are from social interactions. We start defining our value according to how others perceive us and treat us.

At this young age, we’re too inexperienced to be objective, so we personalize and misinterpret a lot of our interactions. At some point in our adolescence, we begin to view our peers in terms of who’s more popular, who’s got the best personality, who’s smarter, who’s more beautiful or handsome, who’s the better athlete? We can feel, Is that person better than me? Or, Am I better than he or she? Self-doubt is an instinctive aspect of human nature, felt by everyone, in varying degrees.

When we can’t feel our deeper value and better self, our inner critic certainly won’t either. Inner conflict becomes more intense when our inner critic assails us for real or alleged failures, while we defend ourselves only weakly through our passive unconscious ego (inner passivity). Often, the inner critic only relents after we have absorbed a lot of punishment that we experience as guilt, shame, anxiety, and depression.

When blocked in our personal self-development, we can feel an accompanying sense of disappointment or failure. The resulting psychological stalemate can provide more “evidence” for why our inner critic is “entitled” to assail us for our real or apparent failings and for our supposed unworthiness. Through our inability to see and understand inner passivity, we can’t appreciate our basic innocence: We would very likely be doing much better if we had access to vital self-knowledge. It’s not our fault that humanity is still relatively unevolved. Nonetheless, our inner critic cares naught about our innocence or naivete. Primitive in nature, it takes advantage of our psychological ignorance to pummel us with self-aggression.

Our inner critic uses comparison as a means of directing scorn, mockery, and condemnation against us. The critic often compares us mockingly with people who are supposedly more skilled, intelligent, or beautiful. As a defense, we now scramble to protect and to validate ourselves by comparing ourselves favorably to certain others. Or we absorb punishment in the form of guilt, shame, and depression by meekly conceding to the inner critic’s allegations. We’re blocked at this point from connecting with our intrinsic, authentic self, the unique greatness within us where we feel and know our goodness and integrity, that inner connection that renders moot all toxic comparisons.

As mentioned, the person engaged in toxic comparisons creates an emotionally and mentally biased separation between himself and others. Out of this arises irrationality, dissension, and even hatred. Hatred of others covers up self-hatred. Our inner critic attacks us scornfully but sometimes also hatefully for allegedly being a lesser person or total loser. Inwardly weak, with only our feeble unconscious ego for protection, we’re at the mercy of the inner critic’s irrational cruelty. We absorb the inner abuse, and then we become a surrogate of our inner critic, radiating malice outward at others, ridiculing them as we are inwardly ridiculed. Hatefulness and anger, with their aggressive thoughts and feelings, serve to create an illusion of strength or power, further covering up underlying fear and making toxic comparisons a compulsive, highly-biased behavior.

In protecting self-image and declining to address inner conflict, people compare themselves to others by making themselves innocent and others guilty. Again, we make such toxic comparisons to “validate” our negative reactions, to buttress our defenses, and to protect our ego. We convince ourselves that our self-generated negative emotions are caused by the “bad” that exists in others. The use of this defense by the mentally ill turns them into ticking time-bombs.

When we take our inner life for granted, unresolved negative feelings about ourselves tend to contaminate our perceptions of politics, society, and culture. The remedy is to learn how to connect with our better self—through therapy, self-knowledge, meditation, charity, service, gratitude, spiritual or religious practices, and whatever works. We can discover our intrinsic goodness and become wise and generous. We’re no longer interested in comparing ourselves to others. The goodness we feel in ourselves is what we now know to be the essence of everyone.

Consciousness of our intrinsic worthiness, when we access it, becomes our foundation, the one truth we know for sure. Using toxic comparisons to orient ourselves in the world no longer makes sense.

—

My latest book has just been published. It’s titled, Our Deadly Flaw: Healing the Inner Conflict that Cripples Us and Subverts Society (2022), and it’s available here in paperback (315 pages) or as an e-book.