I remember, decades ago, hearing my sociology professor express anxiety about the fragility of American democracy. What is she talking about, I thought to myself, scoffing at her worries. American democracy was as solid as the granite faces on Mount Rushmore.

I later looked it up. The four presidents are carved from a granite called pegmatite, which is weaker and more susceptible to cracking than the area’s surrounding granite.

Here we are, the big election looming, and our democracy is in danger of fracturing into rubble if autocratic-minded Donald Trump is elected. Do those who support him not value democracy?

Voting for Trump is, I believe, an act of destructiveness, and I explain further along exactly why this is so.

At our best, we have a feel for democracy that relates directly to how we feel about ourselves. When our best self oversees our inner life, we establish an inner democracy and with it a pleasing sense of inner freedom. Now we understand the value—the imperative!—of democracy: We can feel its richness from within—and we don’t take it for granted.

It’s no surprise democracy is on tilt: Mental health trends are going in the wrong direction. Democracy depends on our collective mental health, yet modern psychology and psychiatry are not showing clearly enough the nature of the dysfunction that undermines our personal relationship with our self. Basically, we resist exposing the dynamics of our inner conflict, that disturbance in the human psyche that produces misery and self-defeat.

We’re limited in our capacity to feel the greatness of democracy and our capacity to preserve it because inner conflict imposes a tyranny upon us. It curbs our inner freedom and our powers of self-regulation. It makes us weak and defensive in the face of our imposing inner critic (superego). Through the passive side of inner conflict, we cede power to the superego. Through our unconscious passivity, we are enablers of the superego. We allow it to tyrannize us.

In denial of this inner weakness, people are prone to react with misplaced anger, hostility, and aggression. This phony, reactive strength covers up our inner weakness, but it sabotages democracy which requires trust, decency, and friendliness.

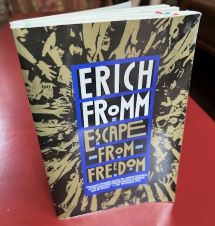

Humanity’s emotional disconnect from inner freedom is a theme in Erich Fromm’s 1941 classic, Escape From Freedom. Fromm claimed that destructiveness is emotionally alluring to many people because it absolves them in an illusionary way of the sense of having failed to meet the challenges of flourishing in a free society. Fromm’s book, published in the UK in 1942 as Fear of Freedom, has not been fully appreciated, probably because of humanity’s unconscious resistance to its central idea. Fromm said many of us harbor too much self-doubt to be comfortable with the sense of freedom that a thriving democracy requires of us.

We are resistant to exploring the full dimensions of this self-doubt because doing so reveals, to our ego’s dismay, our undercover participation in self-defeat and our compulsion to recycle familiar, unresolved hurts from childhood (the first hurts). Inwardly conflicted people can easily feel resentment toward others who are living happily and freely. Backsliders want to hold everyone back, though again they won’t admit this. They react, mostly unconsciously, to the sense that denying the goodness and value of others will ease their guilt and shame at having shortchanged themselves by failing to connect psychologically with their better self.

Lacking this connection, an individual experiences painful, sometimes agonizing, self-alienation. With self-alienation comes the compulsion to feel disconnected from others. Now, national disunity feels more like the natural order. People who are neurotic can be pulled deeper into self-alienation. Relief from the misery can feel impossible through growth and renewal, hence alternatives are unconsciously chosen: cynicism, nihilism, militant ignorance, and an impulse to destructiveness.

In disparaging or destroying the good in the world, people are extending outward their inward destruction of their better self.

Inner conflict can produce the impression that we’re in a losing battle to know our worthiness and goodness. Trapped in inner conflict, we are more likely to be living below our potential. We’re more likely to be incompetent, stupid, even evil. We are compelled to inflict upon the world the negativity that our inner conflict produces within us.

Our main conflict, I believe, pits the inner passivity in our unconscious ego against the self-aggression in our superego. People typically identify with the passive side of inner conflict, which means they are inwardly defensive and passively reactive to their aggressive, largely irrational, and frequently tyrannical superego. In this weakness, they are disconnected from their better self and thereby lack the harmony of inner democracy.

—

With inner conflict comes the tendency to destroy what is good, whether a long-time marriage, a flourishing company, or a world-class democracy. When we decline to connect psychologically with our better self, we hate to see others making progress. Now it’s more likely that people will act or vote against progress, though they will deny this intent, even to themselves.

Many of us experience inner conflict between wanting to be free versus feeling constrained or trapped, between wanting to feel strong versus holding on to feeling helpless. Consciously, we certainly want to feel free and strong and to enjoy that feeling. Yet unconsciously, we can be unwittingly indulging in unpleasant—even agonizing—impressions of weakness, inadequacy, and wrongdoing.

Resolving inner conflict is like solving a puzzle—but most people don’t even know the puzzle exists or they can’t bring it into focus.

An impoverished sense of self is a leftover from the many subjective impressions we experienced as children. It is hard to make our own luck in the world when we harbor unresolved self-doubt, helplessness, unworthiness, self-pity, and victimization. Ideally, we grow out of this weakness and connect with value, truth, and strength.

To cope with inner weakness, many of us desperately seek wealth, fame, and power, which offer us the illusion of being more substantial. This self-doubt explains racism, misogyny, class-pride, nationalism—we get to feel superior to others to cover our emotional entanglement in self-doubt. Behind an anxious desire to be accepted lurks the agony of feeling disconnected from a sense of worthiness.

Fromm writes, the “destructive impulses are a passion within a person, and they always succeed in finding some object.” If an outside object is not available, one’s own self “easily becomes the object.” Now self-rejection and self-hatred (which become rejection and hatred of others) come into play, along with the willingness to abandon personal integrity and honor.

Denying this inner weakness, people often claim, as a defense, that they really want to be strong. Now they might identify with an apparent strongman who, like them, is also hiding a stash of inner weakness.

Fromm writes that destructiveness is the outcome of an unlived life. “It would seem,” he wrote, “that the amount of destructiveness to be found in individuals is proportionate to the amount to which expansiveness of life is curtailed.”

Inner conflict curtails expansiveness. A foremost inner conflict is our conscious wish to be strong and resolute versus our unconscious readiness to know and feel ourselves as flawed or weak. People can get stuck in this conflict because the conflict itself—our inner defensiveness versus the self-criticism we level against ourselves for the “crime” of being flawed or weak—is resistant to being resolved. Feelings of weakness—experienced as entanglements in helplessness, criticism, rejection, and abandonment—are emotional attachments that people unwittingly recycle and replay by way of defensive and incriminating inner voices (sometimes registered consciously, sometimes not).

I believe the biggest attachment of all, the greatest compulsion, is to go on knowing oneself through inner conflict. This means, if true, that many of us are, in some degree, inwardly enslaved. How can we love democracy if we can’t feel fully free? To love democracy and to grow democracy, it’s vital to feel democracy’s essential value within us. That value is the goodness intrinsic to our individual and collective existence.

To know how democracy dies is to know how democracy thrives. Democracy thrives when we understand, individually and collectively, the psychological weaknesses that undermine us. We are lower than we realize on the spectrum of consciousness, and the courage to see what we resist knowing about ourselves becomes the intelligence that moves us forward.

The stronger we are in terms of emotional resilience and mental health, the freer we are. We become increasingly free from worry, fear, anxiety, depression and other disturbances of inner life. Now, able to live harmoniously within, we are more capable of maintaining and growing social harmony and political freedom, which are inherently democratic.