I’ve just published a book of poetry, and the 50 poems in the collection flow with rhythm and rhyme, all to purge the inner strife that so many people endure. (Two of the poems can be read at the end of this post.)

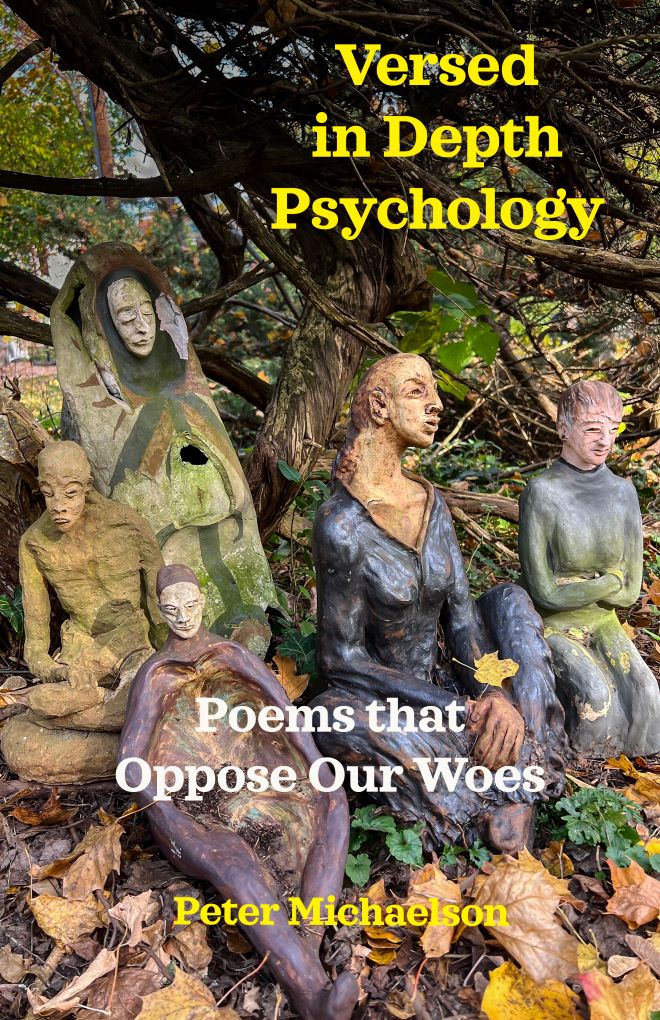

Since the 1980s, my writing has focused on helping people access the vital knowledge of depth psychology. Last summer, I began the effort to communicate this vital knowledge through poetry. This collection is available here in paperback and as an eBook. It is titled, Versed in Depth Psychology: Poems that Oppose Our Woes. The poetry adds up to almost 14,000 words, and the book also includes two prose essays in the Appendix.

Since the 1980s, my writing has focused on helping people access the vital knowledge of depth psychology. Last summer, I began the effort to communicate this vital knowledge through poetry. This collection is available here in paperback and as an eBook. It is titled, Versed in Depth Psychology: Poems that Oppose Our Woes. The poetry adds up to almost 14,000 words, and the book also includes two prose essays in the Appendix.

Strong poetry, I believe, is more likely than prose to slip through our mental zone and penetrate emotional and intuitive realms. Poetry packs wonder and mystery into a little package—so much punch in so few words—and the ensuing magic awakens in us a deeper sense of who we are and who we might become.

I am especially hoping to find readers among young people who are struggling with anxiety, depression, and procrastination.

Poetry tries to reach the deeper you. We can shiver in delight and feel a little wiser after reading Frost, Dickinson, Hughes, and Wordsworth. We feel the pleasure of words that bestir in us a resonance with love and truth. It is said that true poetry, above all, inspires awe. Yes, indeed it does, and that awe arises from poetry’s ability to connect us with our deep self.

Writing these poems, I was inspired by pure pleasure as well as a sense of purpose. The process has been a frolic for me, immensely enjoyable. I have been a prose writer since the 1960s—but not a poet. That I was able to write these poems is evidence for the benefits of acquiring deep self-knowledge. The level of creativity I have achieved in past months, at age 79, contrasts sharply with the mediocrity that haunted me from 1966 to 1984 during my years as a journalist. That was before I discovered, in 1985, the rich vein of depth psychology in the writings of classical psychoanalysis.

Two short poems in this collection were written years ago (among the scattering I’ve written), but the remaining 48 were composed in the nine-month span from July, 2023 through March, 2024, during which time I was a practicing psychotherapist and doing other writing. It was a sweet burst of creativity, and I now intend, after taking a break for a few months, to keep writing more poetry.

The book deals with such topics as inner conflict, psychological resistance, knowing truth from falsehood, and evolving consciousness. Many of the poems are instilled with humor. (The book’s offbeat cover image accompanies the third poem in the collection, “Under the Juniper Tree.”)

After reading the poems, please consider passing them along to young people you know. I believe children as young as 14 years can read this content to help them connect with their pure, essential self.

Here are two shorter poems from the collection:

The Bee Lady

On the street, the loving faces of strolling couples

salt my sorrow, for amid them I perceive how

time borrows hopelessness to bid up my fear

of never finding love. Were love to wink,

I might bump into it, not smite my inert face

on idle lovers doting in their pleasure.

In a dream, I came upon a ghost or sprite,

a lady revenant floating casually, adorned

in garden flowers, swarmed—and loved,

I’d swear—by bumblebees. They buzzed around

and through her, so zany, like Zumba dancers

was it, or sassy Salsa prancers. Her cruel words to me

were the cure, though first they were to slay me.

“Are you a love-seeker,” she spoke, “or a seeker

of feeling unloved?” Though softly said, her words

did sting my sleep. The stinging burned all night,

my heart beat at a frightful rate, my mind did

geminate. Before awakening, I saw in a field

my old self being buried. In this field of clover,

bees procured nectar for the yield of honey.

It was the sweet honey of the Self revealed!

Desolation was buried, too, in the sector

of the field where love was being pollinated.

The Sweetest Misery

Self-pity (grim reverie that tempts a poet

to be witty) is essentially the opposite of giddy.

Do we giggle or cry aloud to see a soul stuck

in a cloud? Self-pity is the sweetest misery.

It’s the consolation prize for composing

a chanson of chagrin—even from romanticism.

Self-pity is finding a pillory in a black cloud’s

relativity. Self-pity is a wail of make-believe.

It’s a tall tale told furtively to claim we aren’t

secretly indulging in feeling refused, helpless,

rejected. Tellers of tales of travesty,

we snuggle up in self-pity’s wily lies.

In self-pity, we beg the court to extend

our trials so we can further indulge in hurt

and passivity. We trick ourself and others

to flagellate us so we can oblige sad fate.

Asking us nicely to fend off self-pity

is like asking Lucifer to forsake his leer.

Perhaps wit, as whetted in this ditty,

can liberate those so needlessly austere.